18‑Month Update – The Future of Iran

Now, Action and Consolidation

Author: Bardia Mousavi

Date: December 2025

Theoretical foundation of the study: the book Dark Zones and the Will to Light

Report on the Situation and Action Strategy

18‑Month Update – The Future of Iran

Now, Action and Consolidation

Author: Bardia Mousavi

Date: December 2025

Theoretical foundation of the study: the book Dark Zones and the Will to Light

______

Copyright Notice

This report is protected by international copyright laws. Any unauthorized copying, distribution, reproduction, adaptation, or publication of any part of this work—whether in print, digital, or any other format—is strictly prohibited. Legal action may be taken against individuals or organizations that violate these rights.

All rights reserved © Bardia Mousavi.

Contents

Focal Status Report on Iran – November 2025, Part One. 5

Section One: Territorial Destruction in Iran. 5

Water crisis: a catastrophe in the making. 5

Deforestation and land degradation. 7

Air pollution: a silent massacre. 7

Section Three: Military casualties of the 12‑day war. 9

Section Four: State Violence by the Islamic Republic (1979–2025) 11

Section Five: Health‑care crisis. 14

Political Action Strategy for the Liberation of Iran. 15

Background and situation analysis. 15

Foundational principles and conceptual framework. 16

Foundational phase: drafting the shared system (Svalbard Model) 18

Phase of consolidating the alternative model 26

Financial resources and funding. 27

Performance indicators and evaluation. 28

Risks and mitigation measures. 28

Preface

The Iran Status Report consists of several component reports that examine the situation in Iran across political, social, and military dimensions. The temporal scope of some reports, such as the twelve‑day war between Israel and the Islamic regime, is roughly six months, while others, such as the assessment of opposition agency from the Mahsa movement to the present, cover a longer period. In each case, the relevant time frame is specified, and the reports are designed so that their distinct temporal windows can serve as the basis for analytical evaluation.

The second part of this research program provides a descriptive account of a political action strategy to overthrow the Islamic regime, structured in three specific phases that are then translated into an operational strategy in the subsequent text. The report proceeds from the assumption, formulated after the twelve‑day war, that the informal ceasefire is unstable because key war aims were not met, and that renewed Israeli military strikes against the Islamic Republic in Iran are therefore likely. These strikes may recur over several intervals until the original war objectives are achieved, while additional power‑shifting variables could emerge and reshape the trajectory of these objectives.

The analysis posits that, for the West, stabilizing an inherently unstable regional order requires ending a pattern of dispersed, low‑intensity conflicts and may thus necessitate engagement in a larger war. The Islamic Republic of Iran is identified as a principal source of regional destabilization in the Middle East; periodic blows may seriously weaken but will not eliminate it. For the first time since the George W. Bush administration, American policymakers appear to have recognized that all other proposed geopolitical “addresses” for resolving the crisis are either incorrect or temporary, and that the only precise locus of hatred and disorder is the Islamic regime in Iran.

The report argues that the region must be reconstructed with a Western‑aligned replacement force, noting that Iran is the only society in the Middle East whose national‑social structure makes it perceive itself as close and co‑fated to the Israeli nation. While citizens in neighboring states reportedly watched the regime’s missile strikes on Israel with enthusiasm in cafés, many in Iran interpreted them as an opportunity for political change. The West is urged not to overlook this potential and instead to use it to strengthen a change‑oriented, democratizing opposition.

The operational strategy and the present reference report recommend investing in the various opposition currents to the regime and propose a form of coordination in which a non‑Iranian intermediary institution establishes, on the basis of a shared‑systems model referred to as the “Svalbard model,” an opposition action group capable of forming a coalition with enabling forces in Israel, the United States, and Europe. The operational strategy seeks to address all executive aspects, including phase‑specific budgeting and key performance indicators, so that this action group can effectively pursue its objectives.

The report further assumes that the Islamic regime in Iran will not capitulate and that, consequently, Israeli military attacks on the regime are inevitable. Embedded within the document is the view that such attacks constitute an opportunity to align with a Western–Israeli coalition, thereby restoring agency to the Iranian opposition and population. This constellation is described as a universally beneficial game for the region and for the people of Iran, enabling them to reclaim control over their political destiny.

Who is the executor of the operational strategy?

The operational strategy in its first phase is premised on constructing a shared system and a regional coalition against the regime. Although the circle of stakeholders is described in the appendices, implementation of the operational strategy at its core step—the creation of the shared system—requires the involvement of a non‑Iranian intermediary institution. Given the depth of existing political cleavages, it is virtually impossible for any of the domestic forces on their own to build a national platform. The experience of the last three years not only confirms this assessment, but also demonstrates the necessity of an innovative form of political radicalism grounded in such a platform.

Both core reports have been translated into English, and Excel files in both Persian and English have been prepared to support operational tracking at each stage. In total, four PDF files in Persian and English describe the operational strategy, complemented by three PowerPoint files in Persian and English for training and presentation purposes. Altogether, the operational strategy comprises fifteen reference files, and, in addition, complete datasets from dozens of CSV files containing underlying data and statistics are available for provision to institutions upon formal request.

Bardia Mousavi — December 2025 — Munich, Germany.

Focal Status Report on Iran – November 2025, Part One

This comprehensive statistical report analyzes and documents Iran’s current situation across several key domains: territorial and environmental degradation, the poverty crisis, the economy, public health, the right to life, and, finally, the military casualties from the 12‑day war with Israel. All data have been compiled from credible international and domestic sources.

Section One: Territorial Destruction in Iran

Water crisis: a catastrophe in the making

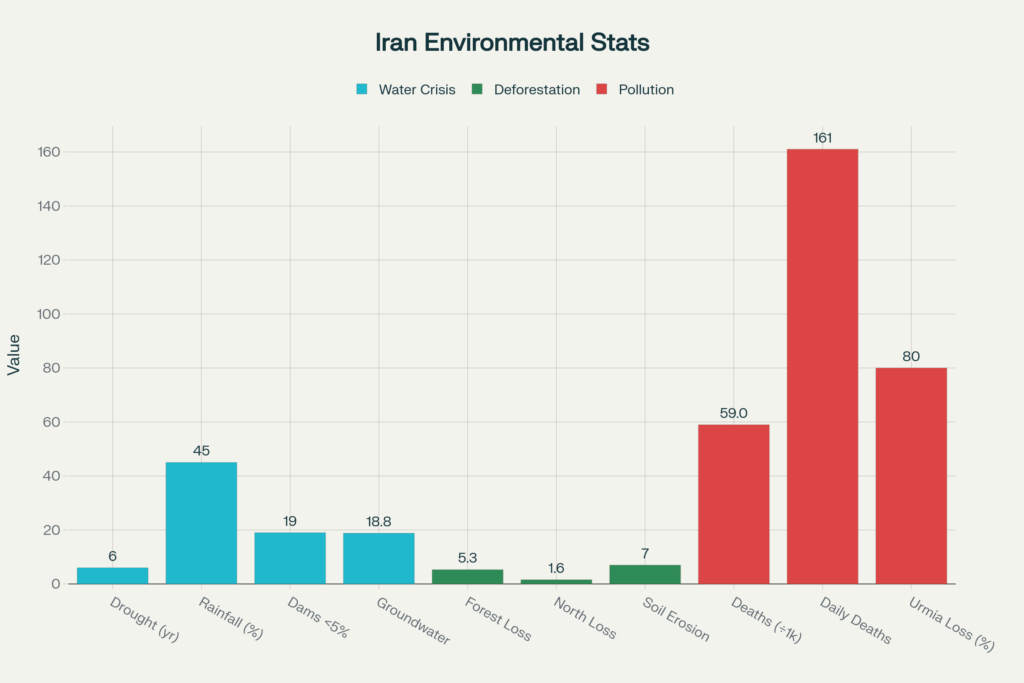

Iran is experiencing its sixth consecutive year of drought (2020–2025), the most severe drought period in the country’s modern history. Precipitation in the 2024–25 water year has fallen to 45% below normal, with some provinces, such as Hormozgan and Sistan‑Baluchestan, seeing reductions of 77% and 72% respectively.

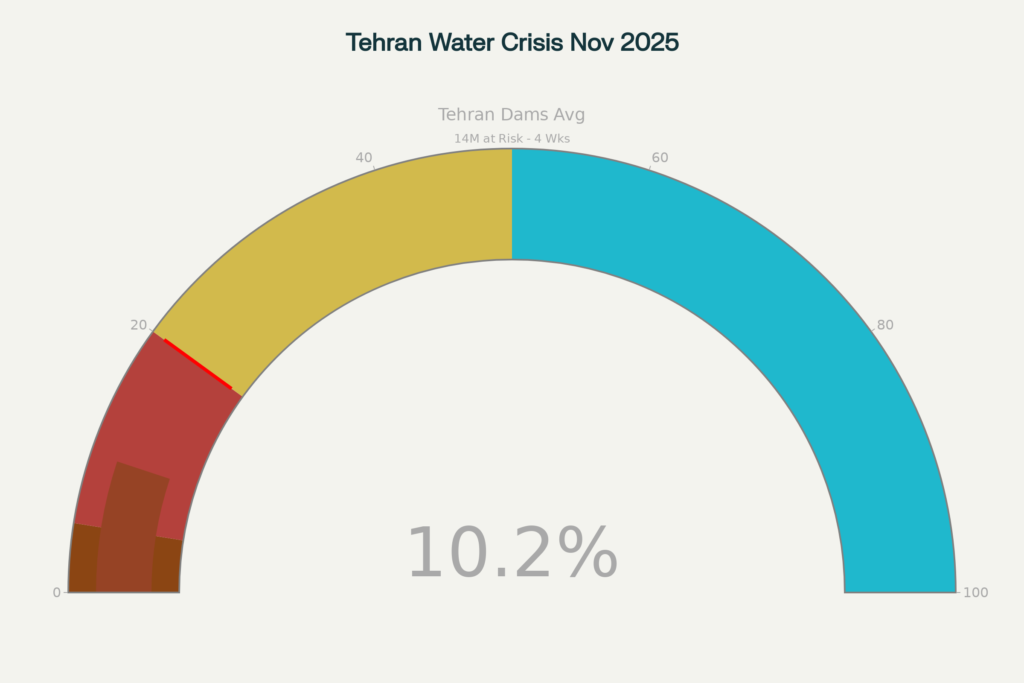

The situation of the country’s dams is catastrophic. Nineteen dams, each operating at less than 5% of capacity, are on the verge of complete desiccation, whereas only nine dams were in this condition three weeks earlier. The five main dams supplying Tehran (Lar, Latian, Karaj, Taleqan, and Mamloo) are on average operating at only 10% of capacity.

Territorial destruction in Iran: water crisis, deforestation, and air pollution

Excessive withdrawal from groundwater resources is one of the most important drivers of the crisis. Each year, 63.8 billion cubic meters of groundwater are extracted, while natural recharge amounts to only 45 billion cubic meters, creating an annual deficit of 18.8 billion cubic meters; this unsustainable withdrawal has led to land subsidence and ecosystem degradation.

Lake Urmia, one of the world’s largest salt lakes, has lost 80% of its volume, with severe environmental consequences for biodiversity and agricultural productivity. Nineteen of the country’s thirty‑one provinces are currently experiencing extreme drought.

Water collapse

Tehran’s water collapse: evacuation of 14 million people by December 2025

Immediate crisis in Tehran:

· 14 million people at risk of evacuation by mid‑December 2025

· Reservoirs at 7–14% of capacity, the lowest level in 60 years

· Latian Dam completely dry

· Thirty‑two national dams below 5% capacity (up from 8 dams in early 2025)

· 96% decline in rainfall in Tehran

· Six consecutive years of drought

All data are drawn from reputable international sources, including Iran Human Rights, the United Nations, Amnesty International, and Reuters.

Deforestation and land degradation

Over the past seven decades (1942–2018), Iran has lost 5.3 million hectares of forest, shrinking from 19.5 million hectares to 14.2 million hectares. The northern forests (Gilan, Mazandaran, and Golestan), among the country’s richest ecosystems, have declined by 1.6 million hectares, from 3.4 million to 1.8 million hectares.

The rate of soil erosion in Iran is seven times the global average: 16.5 tons per hectare per year compared with 2.2 tons per hectare per year worldwide. This erosion removes 500 million tons of fertile soil annually from roughly 15 million hectares of agricultural land, with an estimated economic cost of 50 billion dollars per year.

Seventy percent of Iran’s land area has undergone desertification over the past century. This situation has been exacerbated by misguided agricultural policies, overgrazing, illegal logging, and poorly designed development projects.

Air pollution: a silent massacre

Air pollution in Iran has become a full‑blown public‑health crisis. In 2024, 58,975 people died due to air pollution, equivalent to 161 deaths per day—or nearly seven deaths every hour—representing a 16% increase over the 30,690 deaths recorded in 2023.

In Tehran alone, 7,342 people died in 2024 as a result of air pollution. The cities of Zabol, Iranshahr, and Rigan recorded the highest concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the country.

The economic cost of air pollution is estimated at 2 to 16 billion dollars annually (approximately 2–2.5% of GDP), including health‑care expenditures and lost productivity. The main sources of pollution are industrial emissions, heavy traffic involving aging vehicles, and the burning of low‑quality fuels in power plants and factories.

The poverty crisis in Iran

Poverty statistics: 30 million Iranians in misery

Iran’s national poverty rate in 2025 has reached 36%, the highest level in a decade. This means that nearly 30 million Iranians can no longer meet their basic needs, while the World Bank warns that 40% of Iranians (about 33 million people) are at risk of falling into poverty.

Absolute poverty affects 6% of the population, or around 5 million people, who cannot even afford sufficient food. The World Bank projects that by the end of 2025 and 2026, an additional 2.5 million people will join the ranks of the poor.

Poverty crisis in Iran: 30 million Iranians below the poverty line

According to the World Bank’s benchmark of 6.85 dollars per day for upper‑middle‑income countries, 28.1% of Iranians lived below the poverty line in 2020, up sharply from 20% in 2011.

Income inequality and the vanishing middle class

Iran’s Gini coefficient in 2025 stands at 40.9, indicating a significant level of income inequality. The gap between middle‑income households and the poverty threshold narrowed by 22% between 2017 and 2024, meaning previously stable families are now only one paycheck away from destitution.

Wages and cost of living: an irreparable gap

The government has set the official poverty line for 2024–25 at 6,128,739 tomans per person per month. With an average household size of 3.3 persons, a family needs 20 million tomans per month simply to survive, whereas the official minimum wage for 2024 is only 10 million tomans—less than half of basic needs.

Labor activists have described this official figure as a “death line, not a poverty line.” Food inflation reached 41% in early 2025 and 57.9% by late summer, while prices of basic staples have soared: beans by 250%, chicken by more than 50%, and Iranian rice has tripled in price.

Rural poverty and food insecurity

Nearly 50% of the rural population lives in poverty. More than half of agricultural wage laborers were poor in 2020, compared with 36% of self‑employed farmers. Parliamentary research indicates that by 2022 more than half of Iranians were consuming fewer than 2,100 calories per day.

The economic cost of the poverty crisis is estimated at 2 to 16 billion dollars annually (2–2.5% of GDP).

Section Three: Military casualties of the 12‑day war

Israeli casualties

During the 12‑day war in June 2025, Iranian ballistic‑missile attacks killed 28 people in Israel—27 civilians and 1 soldier—and injured more than 3,000 others. The Israeli Ministry of Health reported that a total of between 3,238 and 3,345 individuals were hospitalized, including 23 who were critically wounded.

Between 9,000 and 18,000 Israelis were displaced from their homes, and dozens of houses were damaged or destroyed. Iran launched around 550 ballistic missiles and roughly 1,000 drones toward Israel; most of the missiles were intercepted by Israeli and U.S. air defenses, with an interception rate of about 90%.

At least 31 ballistic missiles struck residential areas or critical infrastructure, including a power plant in southern Israel, an oil refinery in Haifa, and a university in central Israel. Nevatim Airbase sustained 20 to 32 missile impacts, damaging a hangar and a runway.

Military casualties in the 12‑day Iran–Israel war and destruction of military infrastructure

Iranian losses: a devastating blow to leadership and infrastructure

Iran’s losses were far heavier. Estimates put the death toll between 1,060 and 1,190 people, including 610 civilians and hundreds of military personnel from the Revolutionary Guard and Basij, while the Ministry of Health reported more than 2,500 wounded and tens of thousands of residents temporarily and pre‑emptively evacuating Tehran.

Israeli strikes targeted 18 of Iran’s 31 provinces. At least 30 senior military commanders were killed in the initial 13 June attacks, with more deaths in subsequent days, including:

· Major General Hossein Salami, Commander‑in‑Chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

· Major General Mohammad Bagheri, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces

· Major General Gholam‑Ali Rashid, commander of Khatam‑al‑Anbiya Headquarters

· Major General Ali Shadmani, Rashid’s deputy

· Saeed Izadi, head of the Quds Force’s Palestine Headquarters

In total, eight key commanders and thirty top‑tier IRGC officers were killed. In another official tally, the spokesperson of the Masoud Pezeshkian government announced 1,062 deaths, of whom 276 were civilians, including 102 women and 38 children.

Destruction of Iran’s military infrastructure

The Israeli army estimated that roughly two‑thirds of Iran’s ballistic‑missile launch platforms—about 250 launchers—were destroyed in the strikes, along with around 1,000 missiles, leaving Iran with only 1,000 to 1,500 ballistic missiles and about 100 launchers, a 73% reduction in launch capacity and a 40–50% reduction in missile stocks.

More than 80 of Iran’s air‑defense batteries were destroyed. The Israeli military stated that it had achieved air superiority over western Iran and Tehran, and that no Israeli fighter jets were shot down by the Iranian regime.

Damage to nuclear facilities

The Israeli army stated that its airstrikes inflicted significant damage on Iran’s uranium‑enrichment facilities at Natanz and Isfahan, while the United States targeted the underground Fordow site with heavy bunker‑busting munitions. Dozens of other locations related to the nuclear program—including the decommissioned Arak heavy‑water reactor, the SPND project headquarters, and several centrifuge‑production facilities—were also hit.

At least 15 senior nuclear scientists whom Israel claimed were working on a bomb were killed in the attacks. The Israeli Chief of Staff declared that “Iran’s nuclear program has been set back by years,” while U.S. assessments indicated that Iran’s missile‑production capacity had been crippled and that it would take at least a year to rebuild the destroyed components needed to resume production.

The October 2024 strikes: a limited prelude

Israel’s October 2024 strikes on Iran were far more limited than the 12‑day war of June 2025. Four Iranian soldiers and one civilian were killed, and on 1 October Iran fired about 200 missiles toward Israel, causing one death and several injuries. Damage was limited but highly targeted, focusing on air‑defense systems and missile‑production facilities.

Conclusion

This comprehensive report presents a harrowing picture of today’s Iran: a country grappling with unprecedented environmental crises, widespread and crippling poverty, and severe degradation of its military capabilities. The sixth consecutive year of drought, 58,975 annual deaths from air pollution, 30 million Iranians living below the poverty line, and the destruction of 73% of ballistic‑missile launchers all point to a regime mired in profound crisis.

These statistics not only document the scale of Iran’s overlapping crises, but also highlight strategic opportunities for the international community and the Iranian opposition to work toward liberation, reconstruction, and the creation of a sustainable future for the people of Iran.

Section Four: State Violence by the Islamic Republic (1979–2025)

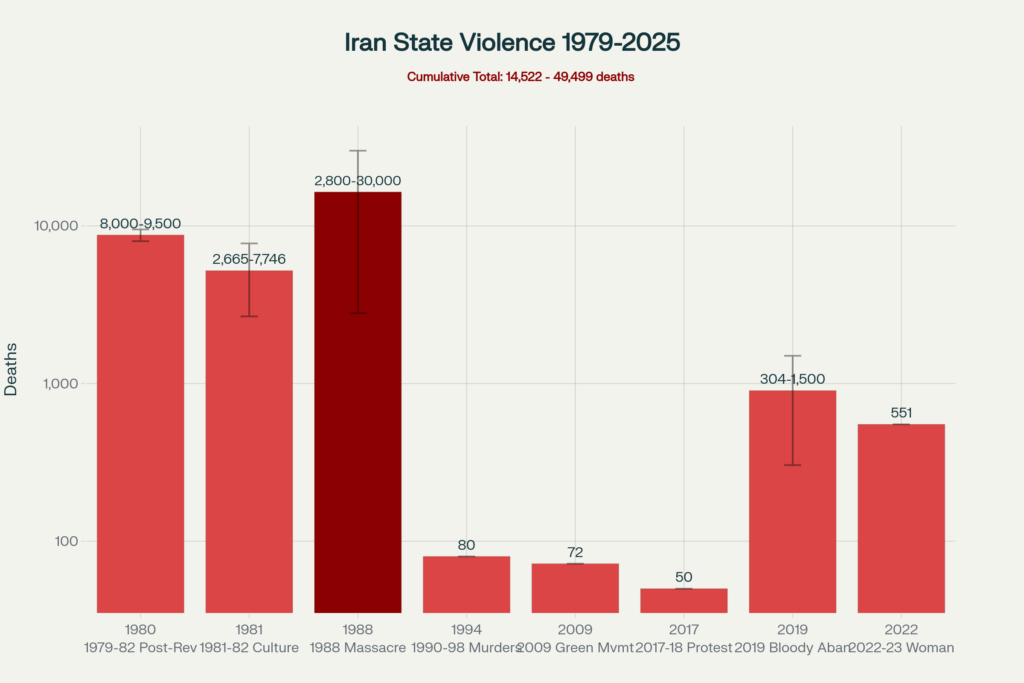

State violence by the Islamic Republic (1979–2025): between 14,522 and 49,499 documented killings.

Key figures: total documented deaths range from 14,522 to 49,499 people.

Major events:

- 1979–1982: Consolidation of power after the revolution

· 8,000–9,500 killed

· Executions by revolutionary courts

· Purge of the former regime and opposition groups - 1981–1982: Cultural Revolution killings

· 2,665–7,746 killed

· Purge of political and religious dissidents

· Classified by the United Nations (2024) as genocide and crimes against humanity - 1988: Massacre of political prisoners

· 2,800–30,000 killed

· Largest mass killing of political prisoners since the Second World War

· Khomeini’s fatwa ordering the execution of all prisoners linked to the MEK

· “Death commissions” in more than 32 cities

· Mass burials in secret graves

· Classified by the United Nations (2024) as genocide and crimes against humanity - 1990–1998: Chain murders

· More than 80 intellectuals killed

· Assassination of writers, poets, and activists by the Ministry of Intelligence

· Methods: staged car accidents, stabbings, potassium injections - 2009: Green Movement

· More than 72 killed

· Post‑election protests

· Neda Agha‑Soltan became the symbol of the crackdown - 2017–2018: Dey protests

· More than 50 killed

· Spread to 160 cities - 2019: “Bloody Aban”

· 304–1,500 killed

· The most violent repression since the 1979 revolution

· Gunfire from helicopters and rooftops

· Total internet shutdown for six days

· Khamenei’s order: “Do whatever is necessary”

· Mahshahr massacre: 40–100 people killed in the marshes - 2022–2023: Woman, Life, Freedom

· 551 killed (including 68 children and 49 women)

· More than 22,000 arrested

· Classified by the United Nations as crimes against humanity

Breakdown by type:

- Revolutionary executions: 8,000–9,500 (19–55%)

- Political massacres: 5,465–37,746 (38–76%)

- Protest killings: 977–2,173 (5–7%)

- Targeted assassinations: 80+ (0.2–0.6%)

Trend in executions in Iran: from 9,557 executions (2008–2024) to more than 1,500 in 2025

Overall execution figures:

· 9,557 executions (2008–2024)

· 975 executions in 2024 – the highest in two decades

· 1,537 executions from October 2024 to October 2025

· 304 executions in November 2025 alone – one execution every two hours

Baluch executions (2021–2025):

Year – Baluch executions – National total – Share – Notes

2021 – 47 – 333 – 14.1% – First year of separate documentation

2022 – 93 – 582 – 16.0% – Double the previous year

2023 – 172 – 834 – 20.6% – Highest figure: 20% of all executions

2024 – 108 – 975 – 11.1% – Still disproportionate

2025 – 150+ – 1,000+ – 15% – Ongoing pattern

Key points on the Baluch: systemic discrimination

· Baluch share of population: about 5% of Iran

· Baluch share of executions: 15–20% of all executions

· Disproportionate rate: three to four times their demographic weight

Cumulative 2021–2025:

· More than 570 Baluch executed

· Most charges: drug‑related offenses

· Region: Sistan‑Baluchestan

· Highest poverty rate in Iran

· Sunni majority (under a Shia state)

Zahedan “Bloody Friday” (30 September 2022):

· 104 Baluch killed in a single day

· Part of the Jina Amini protests

· Sistan‑Baluchestan: 134 killed across all protests – the highest of any province

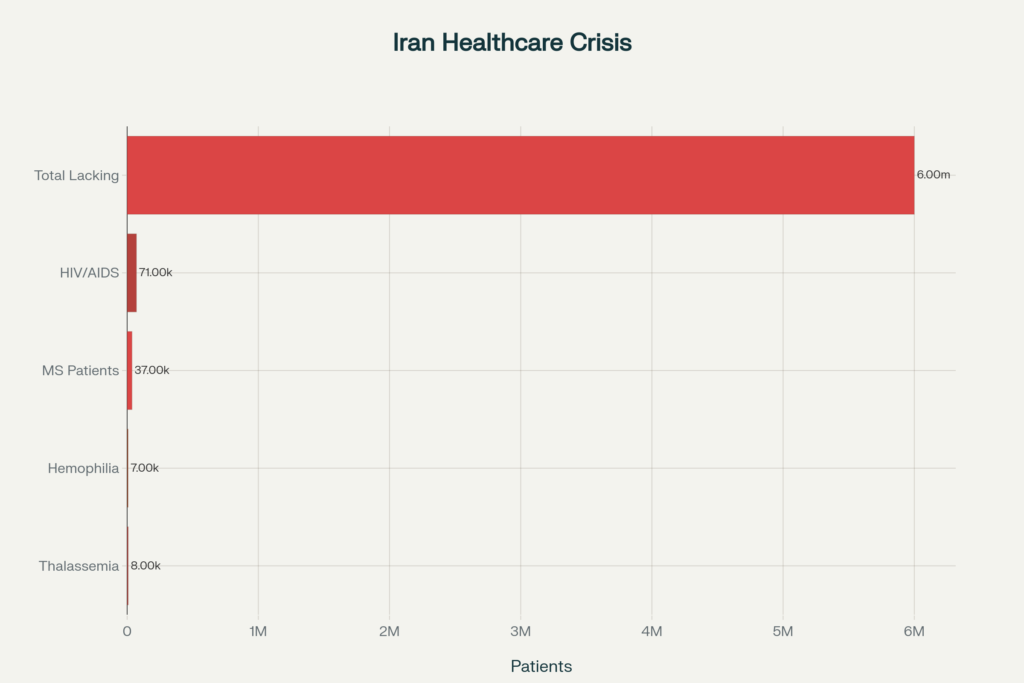

Section Five: Health‑care crisis

Iran’s health‑care crisis: 6 million patients without access to treatment

· 6 million patients lack access to adequate care

· 71,000 people living with HIV/AIDS

· 37,000 patients with multiple sclerosis

· Drug‑price inflation projected at 700%

· 7,000 health‑care workers have emigrated (2023)

· Import costs up 40% (2025 sanctions)

· Severe shortages expected by March 2026

Political Action Strategy for the Liberation of Iran

Executive summary

Overall objective

The establishment of a strong Iranian nation‑state grounded in the separation of powers and liberal democracy through the implementation of a strategic package that combines a shared political‑system model, coordinated operational action, and strategic military measures.

Key difference from previous approaches

Previous strategies of the Iranian opposition (the “Noah’s Ark” model) sought to place all groups in a single coalition. This approach required excessive expansion and illogical compromises, which produced weakness and eventual failure.

The Svalbard Model (Svalbard Seed Bank) proposes a rational system for selecting and safeguarding only those elements that are essential for a viable future for Iran. This model:

· Avoids haste and chaos.

· Emphasizes foresight and evidence‑based problem‑solving.

· Includes only actors that possess the political and intellectual capital necessary for reconstruction.

· Protects those elements for which the centrality of the Iranian question is a defining priority.

Implementation phases

Phase I: Design of a shared system for the structure of Iran’s future state.

Phase II: Strategic actions for liberation and activation.

Phase III: National reconstruction and consolidation.

Background and situation analysis

2.1 Internal contradictions of the Iranian regime

The current Iranian regime contains deep structural contradictions that intensify over time.

First contradiction: hybrid structure

· While the regime ostensibly promotes political participation, in practice it has disabled the executive organizations.

· This duality manifests itself in institutional performance and in the formal separation of powers; the emergence of criminal cults in the economy and their steering of politics is the product of this deliberate design.

Second contradiction: sectarian economic policies and criminal cartels

· These policies secure the interests of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and affiliated institutions.

· They heighten public economic discontent.

· Dependence on China generates significant geopolitical costs.

Third contradiction: cultural and political discontent

· Instrumentalizing repression in peripheral and ethnic regions as a tool to deepen rifts among opponents has itself become a political problem for the opposition.

· The regime promotes the notion of forced resource extraction to sustain a structurally ethnicized “center” of people who support the government and speak Persian—an aggressively unscientific idea that many ethnic groups have nonetheless adopted and used.

2.2 Military and nuclear posture

The regime is committed to:

· Rebuilding its nuclear facilities after the 12‑day war.

· Restoring and further developing long‑range missiles in the months following that war.

· Preserving, at least partially, its regional terrorist capabilities.

Israeli and U.S. strikes have delayed, but not eliminated, these capabilities.

2.3 Status of the opposition

Current weaknesses of the opposition:

· There is no unified vision of Iran; among many who call themselves republicans, attachment to Iran is not a salient value.

· Alignment with the Islamic regime after the 12‑day war has been striking among some groups and activists.

· There is no coordinated leadership between actors inside and outside the country.

· Foreign funding for democracy has declined; no serious external investment exists to support the opposition.

· No broadly accepted cross‑group strategy for regime change has been articulated.

· The republican opposition is often anti‑Western and anti‑Israel.

Opportunities:

· Widespread popular discontent.

· The regime’s economic weakness has reached a critical point.

· Internal contradictions within the regime are intensifying.

· Western support has the potential to be mobilized.

· After the 12‑day war, a large part of the regime’s command structure and repression infrastructure has been destroyed.

Foundational principles and conceptual framework

3.1 Core principles

Principle 1: Iranian civic nationalism

Civic nationalism is based on recognition and respect for an Iranian identity grounded in:

· Shared territorial history and culture.

· Democratic values and human rights for every individual within Iran’s territory.

· Acceptance of religious and ritual diversity, with active protection of vulnerable minorities.

Principle 2: independent separation of powers

The future Iranian state will be built on the separation of legislative, executive, and judicial institutions:

· Legislative branch: a founding parliament in the first stage, followed by a representative parliament.

· Executive branch: an elected head of government with circumscribed powers.

· Judiciary: a fully independent, secular system.

Principle 3: optimal, graduated decentralization

· Central level: a strong national government.

· Regional level: provinces or core economic regions/states.

· Local level: democratic municipalities and village councils.

Decentralization serves to:

· Respect geographic and minority diversity.

· Prevent central despotism.

· Preserve national unity.

Principle 4: secular legal order

A complete separation of religion and state within a secular legal framework:

· Civil law founded on universal human‑rights norms.

· Freedom of worship for all faiths and for the non‑religious.

· Legal equality without religious distinctions.

Principle 5: full transparency

All activities of the state and public institutions must be:

· Transparent and accessible to citizens.

· Subject to systematic public auditing.

Principle 6: limiting individual power

No individual or party may:

· Hold executive power for more than two four‑year terms.

· Exercise absolute control over central authority.

· Exploit the state for personal or partisan purposes.

· A supreme court for the protection of the constitution and limitation of power shall be established.

Principle 7: categorical rejection of secessionism and all forms of decentralization based on ethnicity, lineage, rite, or religion

Any attempt to:

· Partition the country,

· Concentrate power absolutely in a person or group, or

· Deviate from democratic principles

is invalid and unacceptable.

Foundational phase: drafting the shared system (Svalbard Model)

4.1 What is the Svalbard Seed Bank metaphor?

Founded in 2008, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is an ultra‑secure facility carved into the permafrost of Norway’s Svalbard archipelago, built to preserve the world’s agricultural genetic diversity over the long term. It functions as a global insurance policy for food security: should war, climate crisis, natural disaster, or systemic agricultural collapse occur, the stored seeds would allow cultivation to restart. More than 70 countries—from Norway, the United States, Germany, and Japan to states in the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America—participate in the project. Ownership of each sample always remains with the sending country or institution; the Vault merely acts as custodian. Its engineering ensures sub‑zero temperatures and full security even under worst‑case climate scenarios. The facility is a storage site only; no research or genetic modification takes place there. Its mission is clear and vital: to safeguard humanity’s agricultural heritage for future generations in the safest place possible (see: Fowler, C. (2008). “The Svalbard Global Seed Vault: Securing the Future of Global Agriculture,” Agricultural Science, 21(2), 26–29).

The Svalbard metaphor underlines that a shared system need not be invented from scratch. It is a pattern already used daily to democratize and protect political life in prominent global examples. The political “vault” guarantees the implementation of democratic participation at the national level. The design of a shared system is based on proven public‑interest principles, not on the contingent demands of any political camp. It is anchored in the recognition that Iran’s territorial integrity is in existential danger and therefore requires a problem‑solving framework focused on rescue. It is rooted in civility to build social trust, and in measurable reach and impact across the territory so that hope can be meaningfully defined. The system might take the form of a parliament‑in‑exile or a specialized action group for Iran. It is consciously contrasted with the “Noah’s Ark” metaphor to stress that meaningful solidarity for urgent action goes far beyond unnecessary and unproductive coalitions.

Shared system: a template for safeguarding the future in crisis

The Svalbard Vault is more than a physical repository; it embodies accumulated wisdom organized on an open, forward‑looking platform. It offers the most precise metaphor available for designing a shared political system capable of guiding a transition and rising from the ashes to save Iran. Just as the concrete vault in the ice preserves seeds without altering their nature, the shared political system is not meant to impose a particular ideology but to protect the very idea of politics, territory, and the birth of democracy amid instability and collapse.

- Protecting the political sphere and understanding politics as practice rather than engineering

Democracy and human rights are established patterns whose effectiveness has been demonstrated worldwide. The shared political system functions like a secure vault whose duty is stewardship, not ownership.

Just as the Seed Vault does not own the seeds, this political system does not own citizens’ votes or predetermine the content of future parties. It is a neutral yet robust platform that guarantees the possibility of future political competition. It allows diverse political forces to fight the sources of crisis instead of each other and encourages them to set aside, temporarily or permanently, their factional preferences.

- Moving from conditional coalitions to solidarity based on the public good and executable strategy

Many conventional coalitions in the Iranian political sphere fail to reach implementation because they lack strong organizations or because they connect actors with profoundly unequal capacity. When a country’s very existence is at stake, power‑building and organizational optimization acquire clear meaning. This system is built on empirically tested public‑interest principles and long‑term national interests, not short‑term partisan gains. Political groups do not bargain over future power shares but agree on the rules of the game. Each camp recognizes that its own survival depends first on safeguarding “Iran” and its democratic structure. - Problem‑definition for Iran’s rescue: prioritizing territory and fidelity to the principle of limited power

The system’s core is an acute sense of emergency. The shared political system is a response to Iran’s critical condition. Its legitimacy does not (yet) derive from the ballot box but from an unassailable platform of national rescue. Whether in the form of a parliament‑in‑exile or a special action group, its mandate is crisis management and strategic planning for salvation. It may be conceived as a provisional government of national rescue tasked with restoring the vital signs of Iran so that normal politics can resume. - Civility as the infrastructure of trust and hope

Hope cannot be sustained if it is perceived as illusory or unattainable. People become hopeful when they see tangible actions and clear instruments of change. The shared political system must rebuild public trust through transparency and accountability. Rather than issuing declarations, it must design high‑impact actions that reduce the cost of political engagement.

Designing a shared system for a strong Iranian nation‑state that:

· Is rooted in Iranian civic nationalism.

· Enshrines the separation of powers.

· Guarantees optimal decentralization.

· Implements a secular legal order.

4.2 Components of the shared system

4.2.1 Think‑tank institute – Drafting council

Name: Group for the Establishment of the Iranian National State

Composition:

· 25 appointed members from intellectual elites.

· 15 representatives from opposition groups.

· 10 international experts in constitutional design, human rights, and state structures.

· 5 experts in policy architecture and strategy.

Responsibilities:

· Drafting an interim constitution.

· Defining the structure of state institutions.

· Designing the electoral system.

· Specifying the rights and duties of each branch of government.

4.2.2 Specialized working groups

Working Group 1: Political system

· Separation of powers.

· Electoral system.

· Rights and duties of parliament.

Working Group 2: Legal system

· Secular constitution.

· Civil and political rights and freedoms.

· Judicial procedure.

Working Group 3: Economic structure

· Economic policy.

· Taxation and public expenditure.

· Labor rights and social insurance.

Working Group 4: Minority and regional arrangements

· Rights of religious and other minorities.

Working Group 5: Defense and security

· Structure of the armed forces.

· Defense policy.

· Civilian control over the military.

4.3 Drafting process

Stage 1: Research and study

· Comparative analysis of democratic systems.

· Review of Iran’s political history.

· Assessment of the social and political needs of the Iranian people.

· Study of constitutional frameworks in other countries.

Stage 2: First draft

· Preparation of the initial shared‑system draft.

· Deliberation in the drafting council.

· External review by international experts.

Stage 3: Public consultation (one month)

· Circulation of the draft among opposition groups.

· Dialogue with civil‑society representatives.

· Collection of public feedback.

Stage 4: Final version

· Revision based on feedback.

· Final approval.

· Official publication of the shared system.

4.4 Content of the shared system

- Foundational principles

· National sovereignty and citizens’ rights.

· Liberal democracy and separation of powers.

· Human rights and legal equality. - Structure of the legislature

· National parliament: 400 representatives.

· Election cycle: every four years.

· Suffrage: all citizens aged 18 and above.

· Electoral method: proportional representation. - Structure of the executive

· Head of government / chief executive: elected for two four‑year terms.

· Cabinet: mechanisms of parliamentary and/or judicial oversight. - Structure of the judiciary

· Supreme Court: highest judicial authority.

· Public prosecutor’s office: investigation and prosecution of crimes.

· Local and specialized courts.

· Judicial independence from the other two branches. - Secular legal system

· Constitution: foundation of citizens’ rights, not religious doctrine.

· Criminal law: based on international legal standards, not sharia.

· Family law: equality of rights without religious discrimination.

· Freedom of religion: the state is committed to no particular faith.

Strategic‑package phase

The strategic package rests on simultaneity and synergy among different lines of action. The central claim is that none of the components—military, media, or on‑the‑ground mobilization—can provide a sustainable solution in isolation; only a synergistic combination can guarantee a strategy of victory.

- Strategic logic: why a hybrid approach is urgent

The history of regime change in ideological and totalitarian systems such as Iran shows that exclusive reliance on external intervention (without a domestic base) either serves only medium‑term goals or is perceived as occupation, while exclusive reliance on internal protests (without protective support) leads to street massacres. The strategic package is built on a doctrine of comprehensive pressure and a sustainable alternative. It assumes a potential for fundamental change based on the regime’s dual vulnerability: legitimacy and repressive capacity. It also recognizes a crucial constraint: military action must not become chronic or temporally open‑ended.

- Purpose of military strikes: not territorial conquest but disabling and paralyzing the regime’s repressive arm and terminating its nuclear‑missile capability. By destroying air defenses, radars, and IRGC command centers, the war machine loses both the capacity to enact repression and to impose its narrative.

- Communication campaigns and opposition: these actors fill the vacuum. Once the repressive arm is cut, there must be forces ready to occupy the streets and narratives capable of framing the strikes not as foreign aggression but as a real opportunity for liberation.

Understanding urgency: carrying out these actions sequentially would be a strategic mistake. Early military action without opposition preparedness yields chaos and contested succession; opposition mobilization without air cover and degraded repression repeats disasters such as November 2019. Simultaneity is therefore the core of an outcome‑oriented strategy.

- Operational description: trigger mechanism and support

In this strategy, military actions play the role of the “hammer” that strikes the regime’s hardened anvil, while civil forces, street movements, and opposition networks act as the mesh that reorganizes the shattered pieces.

a) Surgical military action to alter the balance of terror

This is not a classical war but a time‑bound surgical campaign. Targeting the remaining political leadership and IRGC/intelligence command sends a clear message: regime elites are no longer immune.

- Psychological impact: the removal of top commanders fractures the chain of command at lower levels. This is the moment when Basij and police forces—who, under section 5.2.4, are offered “financial and security incentives”—become prone to defection.

b) Narrative construction: the war of meaning

Section 5.2.2 is the core of the soft‑power dimension. Using metaphors such as “national reconstruction” and “civic nationalism” acts as an antidote to the regime’s propaganda. Emphasizing the slogan “Make Iran Great Again” (inspired by successful populist models but within a democratic framework) aims to attract the grey middle class whose primary concerns are bread and national pride rather than liberal freedoms. This campaign frames foreign strikes as assistance to hostages, not an invasion.

c) Resource infusion: fueling the engine

Allocating budgets—amounting in total to more than X million dollars, as outlined in section 5.2.3—signals a shift from rhetorical to logistical support. Funding targeted strikes, secure networks, and media provides the lifeblood needed to keep the streets mobilized in the critical days following military action.

- Historical precedent and model adaptation

This strategy—combining strategic air strikes with support for the opposition and domestic resistance—has successful precedents, the most notable being the liberation of France in 1944.

Normandy and the Maquis

- Prior to the Normandy landings, the Allies bombed Nazi railways, radar installations, and command centers for months, directly analogous to section 5.2.1’s focus on destroying repression and radar infrastructure in Iran. The goal was to paralyze the Third Reich’s response capacity in France.

- Simultaneously, the Free French forces and Maquis resistance networks were equipped with Allied funding and weapons (the counterpart of section 5.2.3). They sabotaged bridges, provided intelligence, and destabilized cities from within. Without this internal network, the Allied advance would have been slower and costlier.

- From London, General de Gaulle spoke via BBC radio, reassuring the French that the bombings served their liberation, not occupation—precisely the role envisioned for the liberation narrative to separate the people from the regime.

5.1 Objective

To achieve the liberation of Iran through a combination of:

· Strategic, controlled military strikes.

· Communication and information campaigns.

· Investment in the opposition and civil networks.

· International coordination.

5.2 Components

5.2.1 Strategic military operations

Primary objective: halt nuclear and missile development.

Tactical targets:

o Uranium‑enrichment facilities.

o Missile‑launch platforms.

o Nuclear research centers.

Methods:

o Precision air strikes.

o Use of technologies that minimize civilian casualties.

Secondary objective: destroy repression infrastructure.

Tactical targets:

o Remaining levels of IRGC command.

o Intelligence and security centers of repression.

o Air‑defense and radar systems.

Methods:

o Targeted strikes against key commanders.

o Destruction of strategic equipment.

o Protection of defensive assets relevant to post‑regime security.

Timing strategy:

· Phase 1 (week one): broad strikes to degrade regime capacity.

· Phase 2 (weeks two and three): focused strikes to consolidate gains.

· Phase 3 (second month): follow‑on strikes as required.

5.2.2 Communication and information campaigns

Campaign 1: liberation narrative

Objective: frame military strikes as part of a national‑liberation program.

Core messages:

· Strikes seek to eliminate nuclear and repressive threats.

· Military operations are conducted in support of the Iranian people.

· Liberation is an opportunity for national reconstruction.

Distribution channels:

· Satellite radio and television.

· Social‑media networks.

Duration: from 48 hours before the strikes to 24 hours after.

Campaign 2: stripping the regime of its narrative

Objective: clearly distinguish the oppressive regime from the Iranian nation.

· Development of concise, repeatable key messages.

Campaign 3: defining Iranian nationalism

Objective: articulate civic nationalism as Iran’s authentic identity.

· Development of key messages around shared history, rights, and inclusive citizenship.

Campaign 4: “Make Iran Great Again”

Objective: reinterpret the slogan within a framework of liberation and democracy.

Key messages:

· Iran’s greatness lies in its history, culture, and commitment to human rights.

· Iran’s greatness resides in democracy, freedom, and prosperity.

· Iran’s greatness belongs to all Iranians, not to a criminal regime.

Campaign 5: support for the Iranian people

Objective: demonstrate reliance on the Iranian people as the central agents of liberation.

Core content:

· Liberation is for the Iranian people.

· The Iranian nation is strong and capable of freeing itself.

· International support exists to assist the Iranian people.

5.2.3 Investment in the opposition and civil networks

Section 1: domestic opposition

Investment:

· X million dollars to activate opposition structures.

· X million dollars for media.

· X million dollars for think tanks.

Distribution methods:

· Covert, verified channels.

· Cooperation with opposition networks.

· Support for mid‑level leadership.

Objectives:

· Organizing demonstrations and protests.

· Creating local resistance committees.

· Establishing local control in cities.

Section 2: external opposition

Investment:

· X million dollars for diaspora opposition organizations.

· X million dollars for Persian‑language media.

· X million dollars for English‑language outreach and advocacy.

Section 3: civil networks outside Iran

Investment:

· X million dollars for NGOs.

· X million dollars for civic media.

· X million dollars for human‑rights groups.

Objectives:

· Strengthening civil‑society networks.

· Building capacity for local governance.

· Supporting social institutions.

5.2.4 Financial incentives for elite defection

Objective: encourage defections within the regime.

Mechanisms:

· Offers of political asylum in exchange for cooperation.

· Conditional immunity from prosecution.

· Secret remuneration for information sharing and collaboration.

Budget: X million dollars.

Goals:

· Deepening internal regime splits.

· Weakening regime communication and cohesion.

· Generating pervasive uncertainty within the ruling apparatus.

Phase of consolidating the alternative model

Regarding the post‑overthrow phase of the regime, extensive research already exists, so this report does not devote much time to describing that context in general terms. In this operational plan, the consolidation phase is shaped by acceptance of the narrative and implementation of the shared‑system model, as well as by the interests of the Iranian people and the victors of the war. Nevertheless, and given the logic of simultaneity across phases in terms of the overall theory of change, a proposed model is outlined here, while recognizing that in reality the concrete configuration of victorious forces will ultimately determine how consolidation unfolds.

6.1 Objective of the phase

A provisional government, a constituent parliament, the definition of the shared system, and the establishment of institutions.

6.2 Implementation steps

Step one: creation of a mediation group for institutional founding

Composition:

· 15 representatives of civil forces.

· 25 delegates nominated from the shared‑system platform.

· 5 representatives of the international community (in an advisory role).

Responsibilities:

· Designation of the head of the provisional government.

· Oversight of, and power to dismiss, the provisional government.

· Proclamation of provisional law for the immediate establishment of an executive authority.

· Transfer of interim arrangements to the provisional government.

Step two: drafting, modalities, and implementation of the constituent parliament

Responsibilities:

· Reviewing the shared liberal‑democratic system.

– Defining the operative economic model and recommended political system.

– Defining the secular legal order.

– Drafting the electoral law.

Step three: drafting, appointment, and start‑up of the legal council

- Establishment of the judicial authority.

- Creation of a supreme court for the protection and ratification process of the constitution.

- Design of a transitional‑justice program.

Financial resources and funding

7.1 Total budget for the three phases

· Phase I (design): X million dollars.

· Phase II (liberation): X billion dollars.

· Phase III (consolidation and institution‑building): X billion dollars (first year).

Total: to be determined through detailed assessment.

7.2 Funding sources

State sources

· United States:

· Israel:

· European Union:

· United Kingdom:

· Canada:

· Japan:

Total: to be determined through detailed assessment.

Private and institutional sources

· Various foundations: X million dollars.

· Technology companies: X million dollars.

· Charitable donations: X million dollars.

Subtotal: X million dollars.

Budget allocation

Sector – Share – Percentage

· Military operations – 66%.

· Communication campaigns – 6%.

· Opposition – 18%.

· Civil networks – 5%.

· Defection incentives – 5%.

Total – 100%.

Performance indicators and evaluation

9.1 Indicators for Phase I

Indicator – Target – Actual

Foundational circle – 1 month – —

First draft of the shared system – 2 months – —

Public feedback – 1 month – —

Final version – 1 month – —

9.2 Indicators for Phase II

Military indicators:

· Clarifying the fate of enriched uranium stocks.

· Eliminating long‑range missile bases.

· Dissolving the IRGC.

Social indicators:

· Defining and measuring citizen participation in protests.

· Formation of local resistance groups.

Political indicators:

· Defection or removal of senior state officials.

· Dismantling the repression command network.

· Capture of state facilities and public proclamation.

9.3 Indicators for Phase III

· Establishment of the mediation group.

· Establishment of the legal council.

· Establishment of the constituent parliament.

· Formation of the provisional government.

· Establishment of the judiciary.

· Nationwide elections and the formation of popular sovereignty.

Risks and mitigation measures

10.1 Military risks

Risk 1: civilian casualties

· Description: military strikes may cause civilian deaths.

· Mitigation: use of precision technologies, coordination with the population, and strict protection of civilian targets.

Risk 2: international intervention

· Description: Russia or China may intervene.

· Mitigation: prior coordination with Russia and China, establishment of a no‑fly zone, and reciprocal deterrent threats.

10.2 Political risks

Risk 1: regime re‑formation

· Description: former regime factions may reorganize.

· Mitigation: vetting and lustration, creation of a special task force to dismantle terrorist and Islamist structures, judicial prosecution, and international monitoring and assistance.

10.3 Economic risks

Risk 1: economic crisis

· Description: state collapse may trigger economic turmoil.

· Mitigation: international aid, foreign investment, and urgent political measures to lift sanctions.

Final remark

This political action strategy constitutes a comprehensive blueprint for strategic action aimed at realizing national sovereignty, liberal democracy, human rights, and the establishment of good governance.

A future for Iran

A free and democratic Iran requires a powerful national state and a concrete plan for today.

Appendices

Appendix A – Methodology for analysis, risk, and indicators (KPI)

A‑1. Overall methodological framework

This report is built on a three‑layered framework designed to provide a coherent, reliable, and measurable picture of Iran’s political, economic, social, and security conditions. The three layers are:

- Hard‑data analysis

Use of public and international datasets (UN, World Bank, IMF, WHO, FAO, etc.), alongside trend estimates where official data are lacking. - Structural analysis

Assessment of the structural features of the political system, governance capacity, elite cohesion, security networks, economic resilience, and the capacities of the opposition and civil society. - Scenario modeling

Mapping plausible trajectories of change by combining probabilities, risk scores, and comparisons with historical patterns in similar countries.

A‑2. Selection of key performance indicators (KPIs)

The KPI‑selection process follows four steps:

- Defining the objectives of each operational phase

Phase I: cohesion and capacity‑building.

Phase II: liberation and transition.

Phase III: consolidation and institutionalization. - Deriving measurable indicators

Only indicators that can be monitored monthly or quarterly are retained. - Weighting and prioritization

Each indicator is assigned three scores:

– Strategic weight (0–5).

– Operational feasibility (0–5).

– Reliability of measurement (0–5).

- Final selection of indicators

Indicators with an overall score of 3 or higher are included in the model.

KPI scoring formula

KPI Score = (Strategic weight × 0.5)

+ (Feasibility × 0.3)

+ (Reliability × 0.2)

A‑3. Risk‑analysis method

The risk‑assessment framework uses the standard Probability × Impact (P × I) model and aligns with ISO 31000.

- Probability (P): 1 to 5.

- Impact (I): 1 to 5.

- Risk score (RS = P × I).

Risk‑score classification:

- 1–5 → low risk.

- 6–12 → medium risk.

- 13–25 → high risk.

For each risk, the following are specified:

- Risk owner (responsible institution or individual).

- Mitigation strategies.

- Review cycle (monthly or quarterly).

A‑4. Data sources and validation

Four types of data are used in this report:

- Primary data: international organizations and authoritative statistical databases.

- Secondary data: reputable media and human‑rights organizations.

- Research data: academic articles, university and think‑tank reports.

- Analytical data: modeled trends and historical tests.

Validation steps:

- Cross‑checking against at least two independent sources.

- Examination of 5–10‑year historical trends.

- Analysis of variance and volatility ranges.

- Testing internal consistency (for example, aligning poverty figures with inflation and consumption baskets).

- Excluding contradictory or non‑transparent data.

A‑5. Limitations

This methodology acknowledges the following constraints:

- Scarcity of official data due to state censorship.

- Lack of up‑to‑date statistics in some sectors.

- Divergent definitions across international databases.

- Rapidly changing security environment.

- Partial reliance on secondary reports for sensitive domains.

Appendix B – Referencing framework and data‑validation protocol

B‑1. Source classification

For consistent citation, sources are grouped into three categories:

- Primary sources

Data from reputable international institutions such as the UN, WHO, FAO, World Bank, and IMF. - Secondary sources

Credible international media, human‑rights organizations, and verifiable field reports. - Analytical / research sources

Academic studies, think‑tank reports, and specialized analytical work.

B‑2. Referencing rules

- Every numerical or quantitative claim must have at least one traceable source.

- Sensitive or high‑risk data require at least two independent sources.

- Where estimates are used, the text must clearly state: “This figure is an estimate based on multiple sources.”

- Data without credible provenance are excluded.

- Media reports are accepted only when:

– Confirmed by at least one additional source, and

– Consistent with long‑term trends.

B‑3. Data‑validation process

All data undergo a five‑step validation:

- Cross‑source comparison.

- Trend comparison with previous years.

- Analysis of variance and detection of anomalous figures.

- Assessment of internal consistency.

- Outlier review and correction or removal.

B‑4. Policy for ambiguous data

Three decision levels are defined:

- Level 1: acceptable

Data with clear sources and transparent methodology. - Level 2: footnoted

Data with partial information but some remaining uncertainty. - Level 3: rejected

Figures that conflict with established patterns or lack reliable sources.

Appendix C – Independent review process and Red‑Team assessment

C‑1. Purpose

This process is designed to ensure:

- Logical robustness of the analysis.

- Reduction of potential biases.

- Realism of scenarios.

- Compliance with ethical, legal, and policy standards.

- Avoidance of systematic optimism or pessimism.

C‑2. Composition of the Red Team

The team must be fully independent from the report’s authors and include at least three areas of expertise:

- Independent security analysts.

- Specialists in political transition and democratization.

- Experts in data, statistics, and methodology.

Its primary task is to challenge assumptions, not to endorse them.

C‑3. Evaluation domains

The Red Team assesses:

- Coherence and logic of scenarios.

- Realism of security and military analysis.

- Accuracy of social and economic estimates.

- Analytical blind spots and potential biases.

- Temporal and operational feasibility of KPIs.

- Human and security implications.

- Consistency with legal and policy principles.

C‑4. Review process

The process unfolds in four steps:

- Delivery of version 0.9 of the report so that early drafts are not unduly shaped by the reviewers.

- Three rounds of critique, each covering assumptions, scoring, risks, scenarios, and ethical/operational dimensions.

- A Red‑Team report containing:

– Major objections.

– Alternative interpretations.

– Analysis of risk gaps.

– Structural recommendations. - Revision of the final version, with accepted changes implemented and rejected ones documented with justification.

C‑5. Peer review

In parallel with the Red‑Team process, two independent experts from reputable universities or think tanks review:

- The analytical methodology.

- Logical coherence.

- Sufficiency and traceability of sources.

- Transparency and reproducibility of procedures.

C‑6. Conditions for publication and formal presentation

The report may be published or formally presented only if:

- The Red‑Team process has been fully completed.

- Its results have been incorporated into the final text.

- Peer review has been successfully concluded.

- All figures and claims have undergone full validation.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_scarcity_in_Iran

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/11/12/as-the-dams-feeding-tehran-run-dry-iran-struggles-with-a-dire-water-crisis

- https://www.iranintl.com/en/202511227008

- https://www.ncr-iran.org/en/news/economy/how-many-iranians-live-below-the-poverty-line/

- https://www.ncr-iran.org/en/news/economy/irans-poverty-line-exposed-as-deception-leaving-millions-below-survival/

- https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099110623175541902/pdf/P1777150fa1dcd02108b55086af5f3268f5.pdf

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-israel-iran-war-by-the-numbers-after-12-days-of-fighting/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/October_2024_Israeli_strikes_on_Iran

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iran–Israel_war

- https://www.ncr-iran.org/en/news/economy/irans-water-bankruptcy-a-crisis-manufactured-by-irgc-corruption-not-climate/

- https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/422244/The-significant-deforestation-trend-in-Iran-during-last-7-decades

- https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/70aae432-4a3e-4d96-9083-f0800bd959af/content

- https://www.ncr-iran.org/en/news/society/iran-value-of-soil-and-the-importance-of-its-conservation/

- https://freeiransn.com/causes-of-desertification-in-iran/

- https://iranfocus.com/iran/55095-more-than-35000-pollution-related-deaths-recorded-in-iran-in-2024/

- https://www.newsweek.com/deadly-environmental-crises-iran-tehran-pollution-smog-11087744

- https://www.ncr-iran.org/en/news/irans-lungs-on-fire-wildfires-toxic-air-and-the-politics-behind-an-environmental-collapse/

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12420349/

- https://www.sharghdaily.com/بخش-اقتصادی-12/1063558-پیش-بینی-بانک-جهانی-از-افزایش-میلیونی-جمعیت-زیر-خط-فقر-ایران-در-سال-نرخ-فقر-در-ایران-سال-به-چه-عددی-می-رسد

- https://qudsonline.ir/news/1107286/هشدار-بانک-جهانی-تا-سال-۲۰۲۶-نزدیک-به-۳۹-درصد-ایرانیان-زیر-خط

- https://www.seratnews.com/fa/news/717674/خط-فقر-۱۲-برابری-شد

- https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099126301062574458

- https://www.statista.com/outlook/co/socioeconomic-indicators/iran

- https://www.maxinomics.com/iran/gini-income-inequality-index

- https://www.palestinechronicle.com/israeli-media-over-3000-casualties-billions-in-damage-from-iran-war/

- https://acleddata.com/qa/qa-twelve-days-shook-region-inside-iran-israel-war

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/October_2024_Iranian_strikes_on_Israel

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/liveblog/2025/6/15/live-iran-fires-missiles-as-israel-strikes-oil-facility-in-tehran

- https://www.cnn.com/2025/06/13/middleeast/israel-iran-strikes-military-deaths-intl-hnk

- https://www.rferl.org/a/killed-iranian-generals/33442145.html

- https://understandingwar.org/research/middle-east/the-consequences-of-idf-strikes-into/

- https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/10/26/iran-says-israeli-strikes-on-military-bases-caused-limited-damage

- https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cgr0yvrx4qpo

- https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/505458/Iran-advances-in-Environmental-Performance-Index

- https://www.context.news/climate-risks/opinion/irans-water-crisis-is-driven-by-bad-policies-but-tech-can-help

- https://worldrainforests.com/deforestation/forest-information-archive/Iran.htm

- https://www.worldweatherattribution.org/human-induced-climate-change-compounded-by-socio-economic-water-stressors-increased-severity-of-5-year-drought-in-iran-and-euphrates-and-tigris-basin/

- https://gfzpublic.gfz.de/pubman/faces/ViewItemFullPage.jsp?itemId=item_5036554_3

- https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/125545/1/MPRA_paper_125545.PDF

- https://www.dw.com/en/irans-drought-a-disaster-in-slow-motion/a-74700581

- https://www.cnn.com/2025/11/16/world/iran-drought-cloud-seeding-dry-fall-climate-latam-intl

- https://gssi.it/images/discussion papers rseg/2025/DPRSEG_2025-12.pdf

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC?locations=IR

- https://ijes.shirazu.ac.ir/article_8192_d8f96990aa178694a3879b6a48b676bc.pdf

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/poverty-rate-by-country

- https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gini-coefficient-by-country

- https://gfmag.com/data/economic-data/poorest-country-in-the-world/

- https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/income-inequality.html

- https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099640404212584734

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_income_inequality

- https://pip.worldbank.org/country-profiles/IRN

- https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?locations=IR

- https://data.worldbank.org/country/iran-islamic-rep

- https://www.destatis.de/EN/Themes/Countries-Regions/International-Statistics/Country-Profiles/iran.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=16

- https://qjerp.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-3638-1&sid=1&slc_lang=en

- https://understandingwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/The-Consequences-of-the-IDF-Strikes-into-Iran-PDF.pdf

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/07/iran-israel-iranian-forces-use-of-cluster-munitions-in-12-day-war-violated-international-humanitarian-law/

- https://iranwire.com/en/news/145263-iran-warns-of-deadlier-strikes-on-anniversary-of-missile-attack-on-israel/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_Iran–Israel_conflict

- https://www.iranintl.com/en/202511246646

- https://www.fpri.org/article/2025/10/humiliation-and-transformation-the-islamic-republic-after-the-12-day-war/

- https://www.bbc.com/news/live/c93ydeqyq71t

- https://warontherocks.com/2025/11/chicken-versus-bumper-cars-in-conflict-escalation/

References in part 2:

- https://iran1988.org/1988-massacre/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/01/world/middleeast/iran-protests-deaths.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casualties_of_the_Iranian_Revolution

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1988_executions_of_Iranian_political_prisoners

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_repression_in_the_Islamic_Republic_of_Iran

- https://www.timesofisrael.com/1500-people-said-killed-by-iranian-security-forces-in-protests/

- https://www.axios.com/2019/12/23/iran-protests-death-toll

- https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2020/05/iran-details-released-of-304-deaths-during-protests-six-months-after-security-forces-killing-spree/

- https://rsf.org/en/iranian-official-accused-1988-massacres-political-prisoners-including-journalists-goes-trial

- https://iranwire.com/en/politics/110511-did-you-know-timeline-of-violent-suppression-of-protests-in-iran/

- https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/un-says-iran-executed-over-900-people-2024-including-dozens-women-2025-01-07/

- https://www.ynetnews.com/article/hymdksci1x

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chain_murders_of_Iran

- https://time.com/6983058/global-executions-iran-amnesty-international/

- https://www.ecpm.org/app/uploads/2025/02/Annual-Report-on-the-Death-Penalty-in-Iran-2024.pdf

- https://iranwire.com/en/features/65674/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019–2020_Iranian_protests

- https://www.iranintl.com/en/202402017433